“For the Church, pilgrimages, in all their multiple aspects, have been a gift of grace.” Saint John Paul II

Watch video introduction here

Saint Mary Major is one of the four papal basilicas of Rome. The other three are St. Peter’s, St. John Lateran and St. Paul’s Outside the Walls.

A PLACE OF MARIAN DEVOTION

As the name suggests, the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore is the largest of the 26 churches in Rome dedicated to the Virgin Mary. As for its age, the archpriest of the basilica, Cardinal Stanislaw Rylko, wrote in 2018 that St. Mary Major is “the oldest Marian shrine not only in Rome, but in the whole West.” According to a legend, Mary is said to have appeared in 352 to Pope Liberius and to a wealthy man named John Patricius. She invited them to build a church on a spot where snow had fallen, although it was midsummer. The incident happened on the night of August 4th to the 5th, on the top of the Esquiline Hill (one of the seven famous hills of Rome). The snow defined the spot where the basilica was to be built. Supposedly, it was paid for by John and his wife. To commemorate this event, every year on August 5th, a shower of white petals falls from a hole, made for this purpose, in the ceiling of the basilica. Documents refer to this basilica as the Liberian Basilica or St. Mary of the Snows, although no trace of this fourth century structure remains. The spot where Liberius built his structure remains a matter of dispute.

Research shows that the earliest part of the basilica dates from the time of Pope Sixtus III (432-440). The present basilica dates back to the fifth century and was started no earlier than 420, maybe with the demolition of the Basilica of Pope Liberius, if it was in existence at that time. Its construction was tied to the Council of Ephesus of 431 AD, which proclaimed Mary Theotokos, Mother of God.

In 432, Sixtus III richly beautified the structure to commemorate the Declaration of Mary’s Divine Motherhood by the Council of Ephesus. The Council stated that Jesus was one person and not two separate persons, yet possessing both a human and a divine nature, and that the Virgin Mary was to be called “Theotokos,” a Greek word which means “God-bearer” (the one who gave birth to God). There is a syllogism that has been used to explain this doctrine: Major premise: Jesus is God; Minor premise: Mary is the Mother of Jesus; Conclusion: Mary is the Mother of God.

The basilica has two facades. The main façade of the basilica was designed and constructed by Fernando Fuga from 1741-1749, before the Holy Year of 1750, during the pontificate of Benedict XIV. It has five entrances, like St. Peter’s, and a balcony or loggia, for papal blessings, also like the Vatican basilica. It also has a bell tower, the highest in Rome at 240 feet. In front of this façade stands a tall marble column, the only one remaining from the Basilica of Maxentius. At the top there is a bronze statue of the Mother and Child. At the foot of the column is a fountain, a reminder to us to drink from the Source of grace, whose mother is Mary. The other façade, located on Piazza Esquilina, has twin cupolas and in front of it stands a Roman obelisk from the Mausoleum of Augustus, dating to the first century.

Let us enter the Basilica through the main façade. The nave or central aisle (fifth century) is 280 feet long and, like ancient Roman basilicas, is divided into a nave and aisles. The nave and aisles are divided by columns of Athenian marble. On the walls of the nave are 36 mosaics of Old Testament history from the time of Sixtus III (fifth century). The mosaics on the right depict Moses and Joshua, while those on the left show scenes from the lives of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob.

The ceiling, which is the work of Giuliano da Sangallo, is composed of 105 coffers, decorative sunken panels in the shape of a square. The coffered ceiling is said to be gilded with the first gold from the New World, a gift of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain.

ROME’S BETHLEHEM

Elizabeth Lev, an art historian, describes the Basilica of St. Mary Major as Rome’s Bethlehem. As we have mentioned, it is dedicated to the God-bearer. Looking at the fifth century mosaics on the triumphal arch, we see that they center on the mystery of the Incarnation of Christ, portraying episodes from the birth and childhood of Our Savior.

Under the high altar of the basilica is the Crypt (confession) of the Nativity or Bethlehem Crypt where we see the crystal reliquary, designed by Giuseppe Valadier, said to contain wood belonging to the Sacred Cradle of Jesus. In the 12th century (Rev. Daniel Thelen, Saints in Rome and Beyond, p. 43), St. Jerome’s relics were brought to the basilica from the Bethlehem cave where he had died and was placed next to five highly venerated pieces of wood, four wooden planks from the manger of Jesus and one that belonged to an ancient picture of the nativity. Scientific investigations have established that the wood of the four planks is compatible with that of a maple tree grown two thousand years ago in Palestine. Up to the last century, these relics from Christ’s birth were located in the crypt (confession) in the chapel to the right of the main altar, that is, the Blessed Sacrament Chapel. However, during the pontificate of Pius IX (1846-1878), the relics were removed and placed in the crypt (confession) under the main altar. It is not certain if the relics of St. Jerome were also moved at this time.

At the beginning of Advent 2019, Pope Francis wanted to give a gift to the Christians of the Holy Land. He sent to Bethlehem a fragment of the manger of the baby Jesus. The Apostolic Nuncio to Israel and Cyprus, Monsignor Leopoldo Girelli, said, “The return to Bethlehem of this sacred wood may arouse in us the deep desire to be bearers of God. Now it is our heart that is a manger: Sacred Cradle of God made man.” The gift is under the care of the Custody of the Holy Land. The Custos (Guardian) Friar Francisco Patton replied to Monsignor Girelli, “Please assure Pope Francis that we will not limit ourselves to guarding this relic, but we will ensure that it represents the outreaching Church and that it brings the joy of the Gospel, making pilgrimages to the various Christian communities of the Holy Land to revive faith in Jesus.” The relic is now located in the Church of St. Catherine of Alexandria, the Latin rite parish of Bethlehem, which is next to the Basilica of the Nativity in Bethlehem.

Leaving the crypt by a stairway, we pass the kneeling statue of Pope Pius IX, who defined the Immaculate Conception. The statue faces the reliquary. Above the crypt is the high altar or papal altar, as we see at the other papal basilicas, and is reserved for the Pope although others may be granted the privilege of using it. The canopy or baldachino above the altar, by Ferdinando Fuga (c. 1740), has columns of porphyry and bronze. In the porphyry urn that makes up the base of the high altar there are relics of St. Matthias, the apostle chosen to fill the place left by Judas (Rev. Daniel Thelen, Saints in Rome and Beyond, p. 43).

The mosaic in the apse is late 13th century by the Franciscan Friar Jacopo Torriti, who also did the mosaic in the apse of the Lateran. The style is different from Eastern tradition of Ruler and Teacher; here Jesus is with Mary, crowning her and sharing his throne with her. They are surrounded by a great blue orb, representing the universe, filled with stars and sun and moon. The orb is supported by angels and flanked by saints. However, we see the traditional eastern elements of the fan-like ornament at the crown of the apse, the foliage among which nestle peacocks and other birds, and at the base, the River Jordan (regarded as the birth-place of the church). Between the four windows the mosaic continues with scenes from the life of Mary.

The arch above the apse dates to the 5th century. The subjects of the mosaics come from the Apocalypse, such as, the Lamb of God, and the 7 candlesticks for the 7 churches to whom John sent his book of visions.

To the right of the high altar is the Blessed Sacrament Chapel or Sistine Chapel. Pope Sixtus V (1585-1590) commissioned Domenico Fontana to construct a chapel of the Most Blessed Sacrament Chapel which could also house the Nativity Scene.

Back in the fifth century, Pope Sixtus III had created within the primitive basilica a “cave of the Nativity” similar to that in Bethlehem. During the centuries that followed several popes took care of Sixtus III’s Holy Cave, until Pope Nicolas IV, the first Franciscan Pope, in 1288 commissioned a sculpture of the “Nativity” by Arnolfo di Cambio.

When Pope Sixtus V in the 16th century wished to erect the large Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament to the right of the high altar, he ordered the architect Domenico Fontana to transfer the ancient fifth century “cave of the Nativity” with its surviving element of Arnolfo di Cambio’s sculpture of the 13th century. They were placed in the crypt of the Blessed Sacrament Chapel along with the relics of the Crib of Jesus and the relics of St. Jerome. As mentioned above, Pope Pius IX in the late nineteenth century then moved the relics of the Crib to the crypt under the papal altar.

On the side walls of the Blessed Sacrament Chapel are the funerary monuments of Sixtus V and the Dominican St. Pius V, the Pope who encouraged the faithful to pray the rosary when the Ottoman Empire threatened to overtake Europe. After receiving word that the Christian forces had defeated the Ottoman navy at the Battle of Lepanto, Pius V promulgated the short prayer, “Mary, Help of Christians” and added a new feast day to the Roman Calendar. October 7th would be the Feast of Our Lady of Victory. His successor, Pope Gregory XIII, in 1573 changed the name of this day to the Feast of the Holy Rosary.

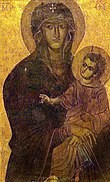

To the left of the high altar is the Pauline Chapel or Borghese Chapel. This chapel was designed in 1611 by Flaminio Ponzio by order of Pope Paul V, a member of the Borghese family. It was built to enshrine the famous icon of the Madonna known as the Salus Populi Romani, or Health of the Rome People or Salvation of the Rome People. It was painted by an artist of uncertain date and traditionally attributed to St. Luke. It is at least 1000 years old. According to Elizabeth Lev, it was more likely that the icon “was here in the 6th century and that Pope St. Gregory the Great carried it in procession through the city to rid Rome of the plague. Thus, for 1400 years, this Marian image has watched over the health (salus) of the Roman people.”

Eugenio Pacelli offered his first Mass on the altar of this chapel on April 3, 1899. Forty years later he was crowned in St. Peter’s Basilica as Pope Pius XII.

Flaminio Ponzio also designed the tomb of Pope Paul V, and Pietro Bernini worked on the decorative sculpture in the Borghese chapel. Here, Cardinal Scipione Borghese discovered fifteen-year-old Gian Lorenzo (1598-1680) working for his father Pietro and took on the role as his patron. The young Bernini became a famous architect, sculptor and painter, whose works of art are known throughout the world. He was so attached to this basilica that he asked to be buried here. In the floor to the right of the high altar is the simple tomb of Gian Lorenzo and his family. The inscription reads: “Gian Lorenzo Bernini, the glory of the arts and of the city, humbly rests here.” And the words, “the Bernini family awaits the resurrection here” were added by Pope Benedict XIV (1740-1758) when in 1746 he conferred the status of nobility upon the Bernini family.

There is much more to see, but we will end here with this piece of art. It is the statue of Our Lady, “Ave Regina Pacis,” which is situated on the left aisle of the basilica, between two side chapels. Pope Benedict XV (1914-1922) commissioned this sculpture in 1918 as a sign of gratitude to Mary for the close of World War I, which officially ended on November 11, 1918. Our Lady sits majestically on her throne. The Child Jesus stands on her lap holding an olive branch, the symbol of peace. At the base of the throne is another sign of peace: a dove with one wing uplifted toward the Mother and Child. Mary’s left arm is outstretched, her hand and palm open, as if to say, “Stop, no more war!” At the same time, she seems to be protecting us and warding off all danger (Ellen Mady, Aleteia, 5/21/18).

POINTS FOR REFLECTION:

*Both the Salus Populi Romani and the Ave Regina Pacis, and the entire Basilica of St. Mary Major are a constant reminder of Mary’s faithful presence in the Church, as Mother, as Protectress, and as one who is always pointing us to the Lord.

-How has Mary been Mother to me in my life?

-How have I felt Mary’s presence and motherly protection, especially during these difficult times of the pandemic?

*The title of Our Lady as “Mother of the Church” emphasizes Mary’s role in giving birth not only to Jesus but also to His Church. As Hans von Balthasar said, “Mary’s ‘yes’ makes possible the Church.” As Mother of the Church, Mary shows us the way along the path she has already completed. If we follow the way of Mary, we will journey to the Heart of Christ.

-How has Mary led me in my religious life to the Heart of her Son?

*Pope Emeritus Benedict XIV loves calling Mary “the woman of the yes.”

-With my “yes” to living my religious vows, how am I bringing Christ to birth in the Church and in the world?

*What do my Constitutions say about Mary, the Mother of Christ? What does my Rule say about her? For example, in the Rule and Life of the Brothers and Sisters of the Third Order Regular of St. Francis, we read: “The brothers and sisters should keep the example of the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Mother of God and of our Lord Jesus Christ ever before their eyes. They should so do this according to the exhortation of St. Francis who held Holy Mary, Lady and Queen in highest veneration since she is the Virgin made Church. They should also remember that the immaculate Virgin Mary, whose example they are to follow, called herself the handmaid of the Lord” (Number 17).

-How do I imitate Mary in the way that our Constitutions or Rule speak of her?

-How do I exercise humility? Mary responded to the Angel Gabriel, “Behold the handmaid of the Lord.” The Greek word used in Luke 1:38 for “handmaid” is “slave” (δουλη, doule). I turn to Mary and ask that she may give me a share in her humility.

*Do I have a form of the name of Mary or a title of Mary in my religious name?

-Am I living out my name and my imitation of her?